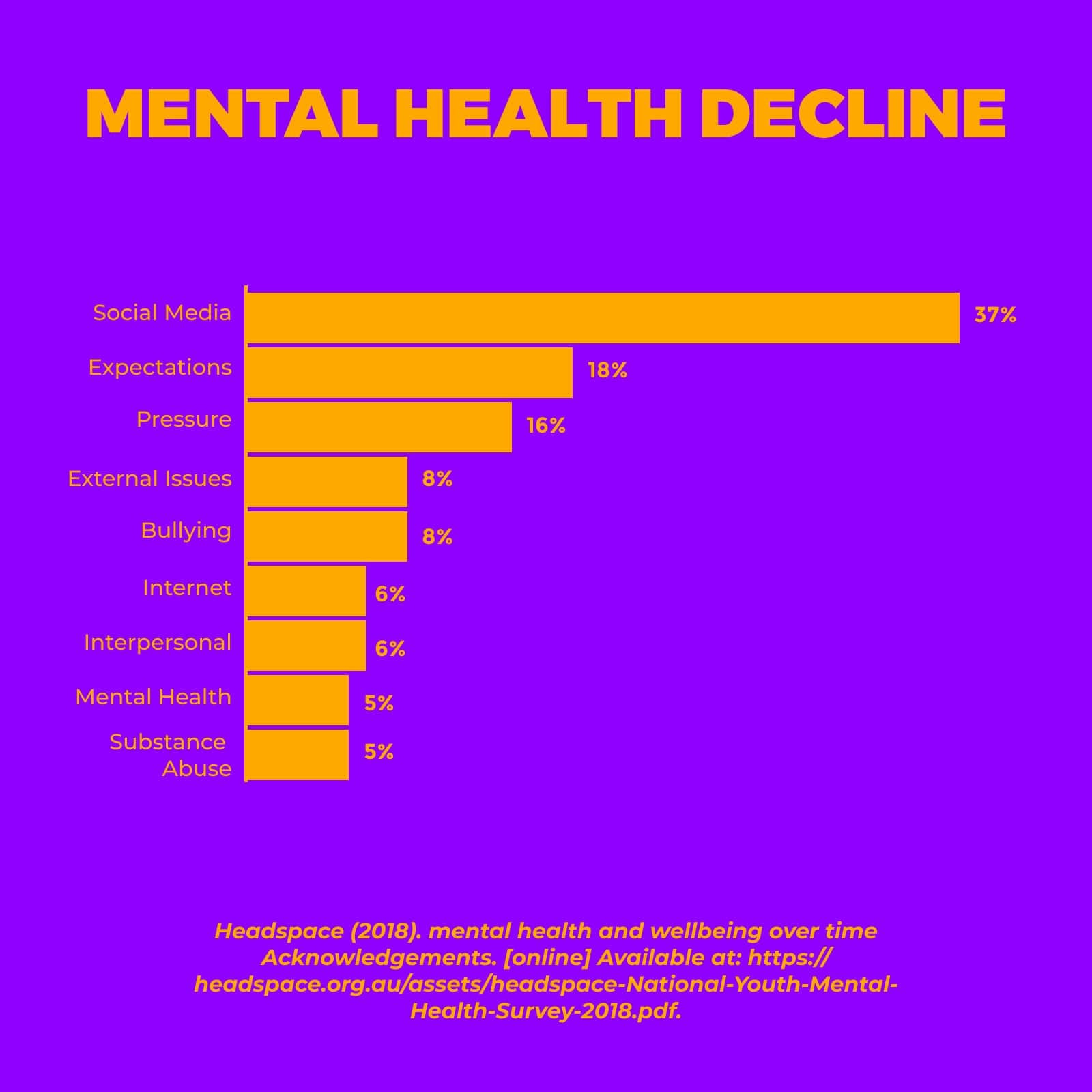

What exactly is it about social media that fuels rising anxiety, depression, and suicide in teens? Can we trace these emotional outcomes back to specific interactions on these platforms? And can we measure the level of toxicity embedded in their design?

We often hear that social media harms our mental health, but vague warnings aren’t enough. I wanted to understand the how and why. Could we identify the actual design choices behind this crisis—and more importantly, imagine better ones?

When I couldn’t find the answers, I began my own research. What followed became the first in-depth attempt to map mental distress to common user interactions. This is what I discovered—and where I believe we can go from here.

First, the benefits.

Social media isn’t all bad. It offers access to stories and expert advice, emotional support and online communities, a space for self-expression and identity, the ability to connect, maintain, and grow relationships. These are meaningful contributions, but we still need to ask: how does mental illness show up in these spaces?

Isn’t social media just a modern version of newspapers?

Not quite. The toxicity of social media runs deeper and to understand why, we need to look at how our nervous system reacts to constant stimuli.

Let’s start with the stress response. It’s a healthy, necessary reaction—designed to kick in if we’re face-to-face with a lion. Our body floods with adrenaline, our heart rate spikes, and blood rushes to our muscles. This system keeps us alive in moments of danger.

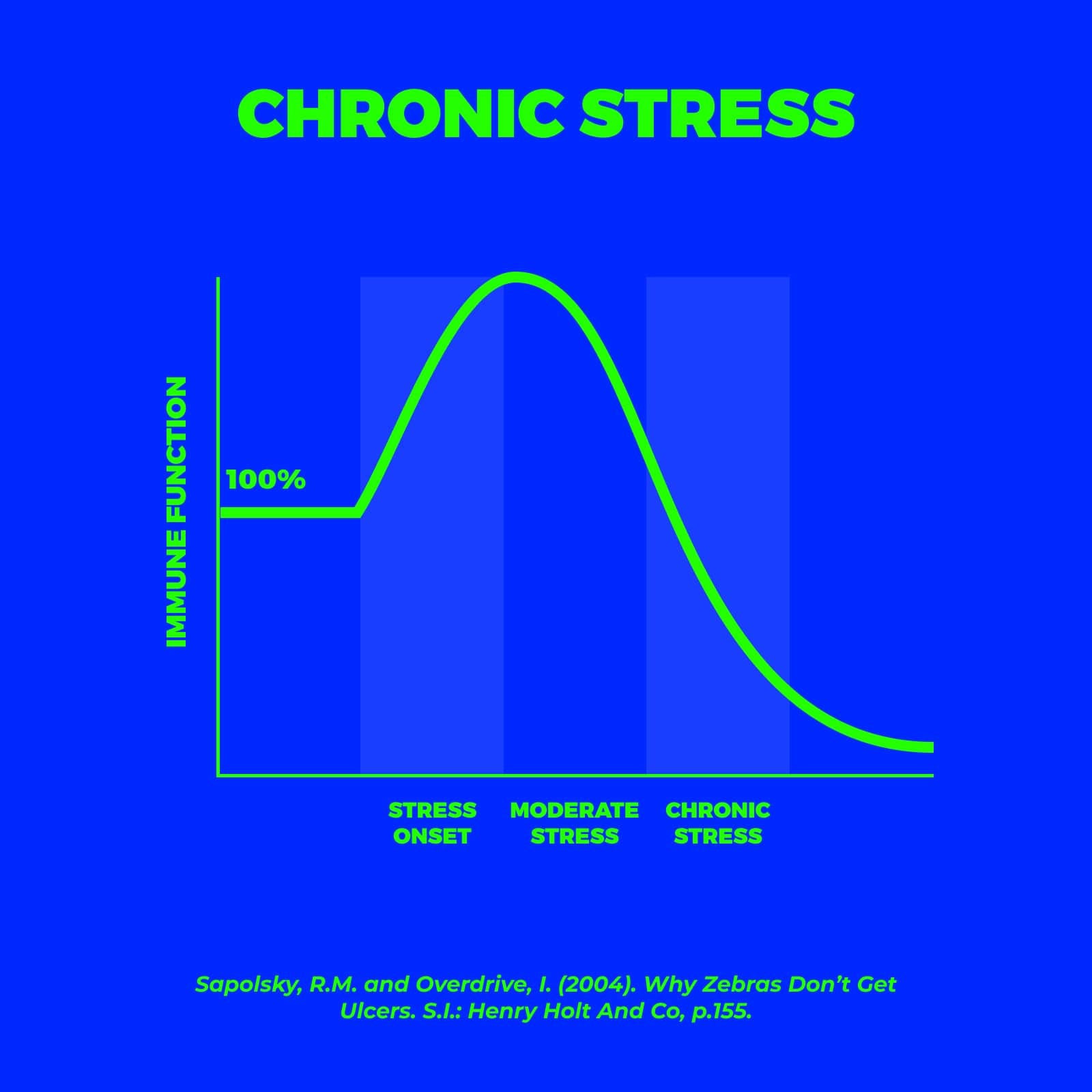

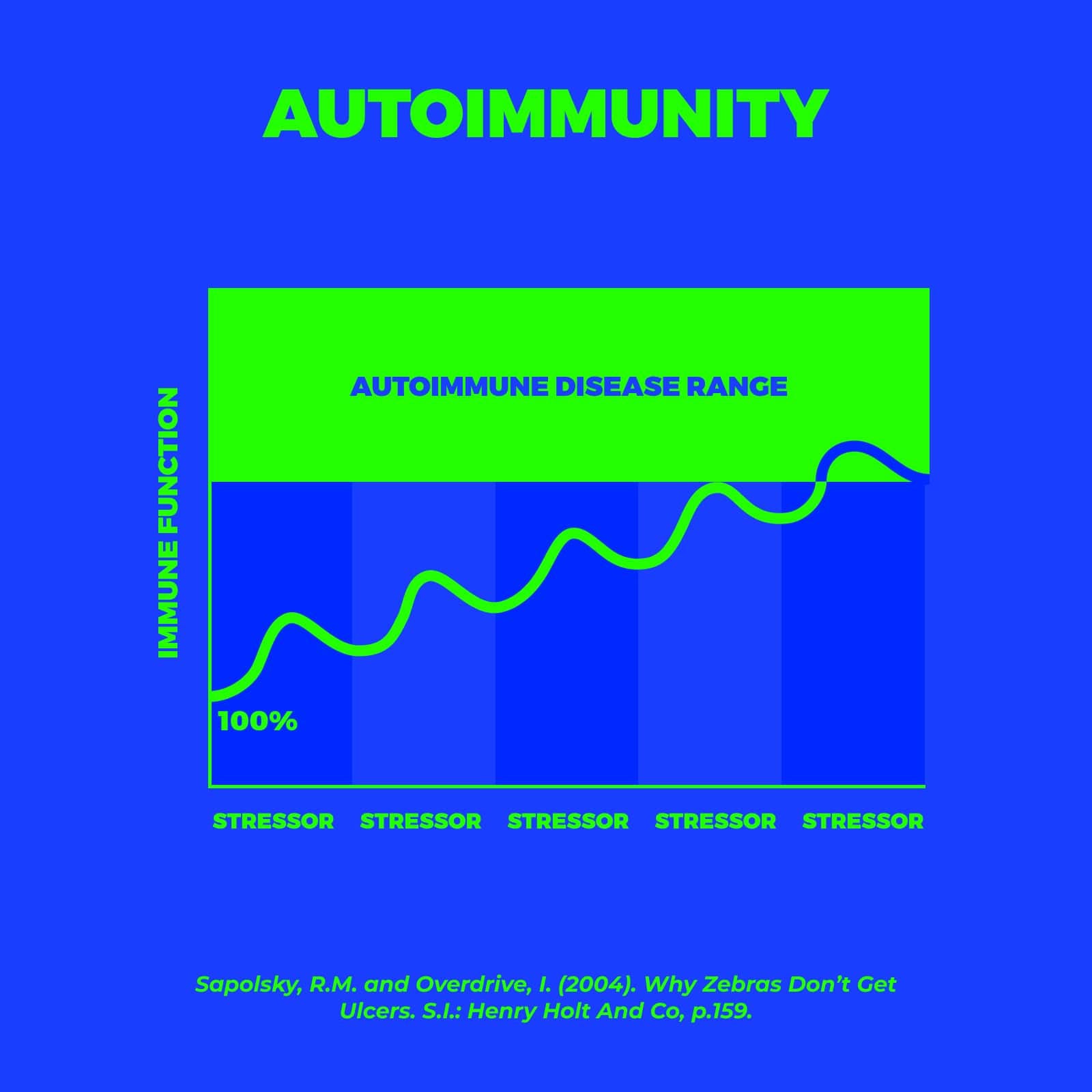

Reading a newspaper might activate this response a few times a day. But social media hits differently. The constant stream of updates—outrage, comparison, conflict—keeps us in a state of low-level stress around the clock. This chronic activation wears us down. Over time, it weakens the immune system, making us more vulnerable to illness.

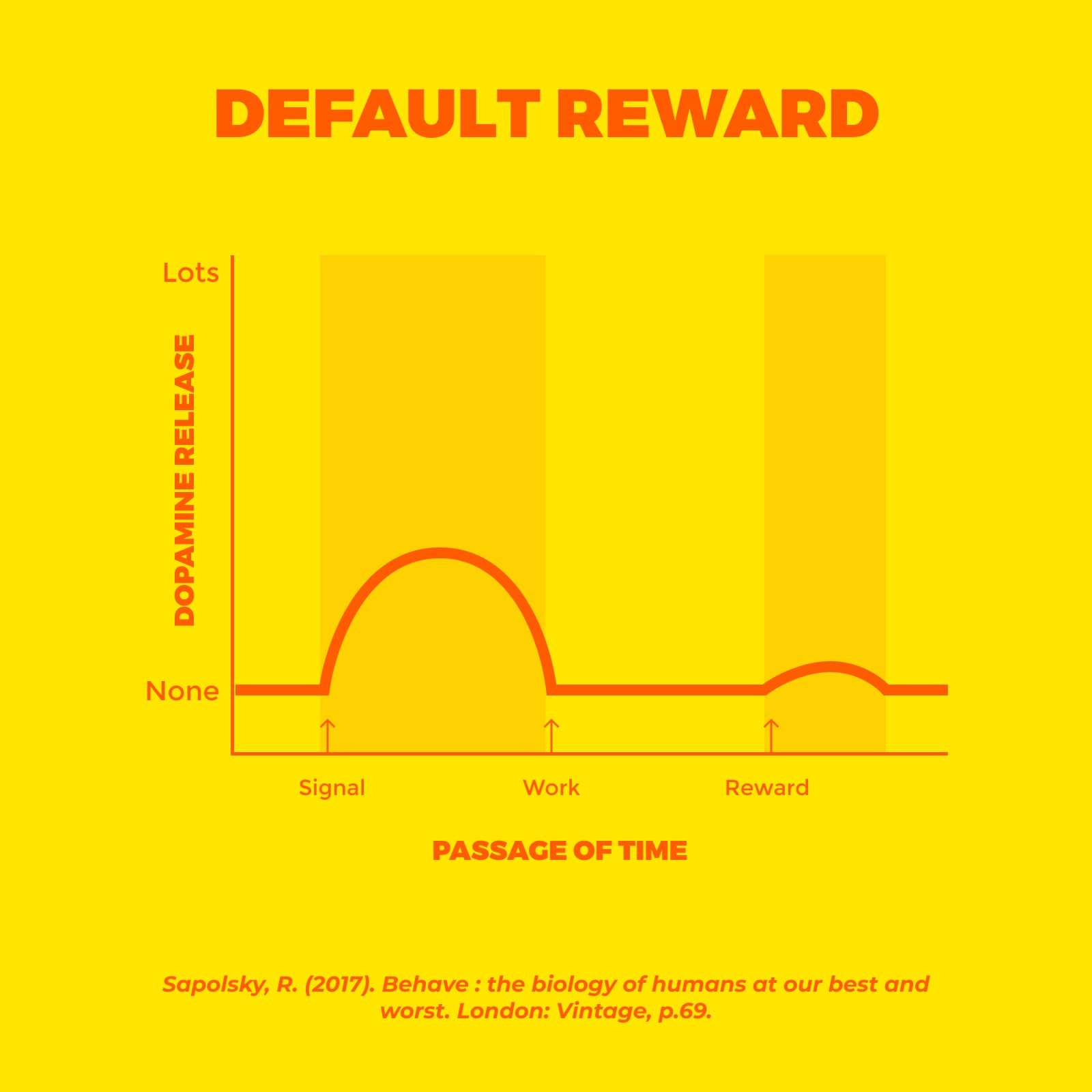

Now dopamine. It’s often described as the “feel good” chemical, but it’s really about motivation and reward. Social media, gaming, porn, and endless scrolling flood our system with it. But the brain adapts. With chronic overexposure, our baseline drops. We feel less pleasure, more anxiety, and are more prone to depression. As with Newton’s third law: for every spike, there’s a crash.

Understanding these mechanisms isn’t about blaming individuals. It’s about designing platforms that work with our biology—not against it.

If happiness is determined by expectations, then two pillars of our society — mass media and the advertising industry — may unwittingly be depleting the globe’s reservoirs of contentment. If you were an eighteen-year-old youth in a small village 5,000 years ago you’d probably think you were good-looking because there were only fifty other men in your village and most of them were either old, scarred and wrinkled, or still little kids. But if you are a teenager today you are a lot more likely to feel inadequate. Even if the other guys at school are an ugly lot, you don’t measure yourself against them but against the movie stars, athletes and supermodels you see all day on television, Facebook and giant billboards.

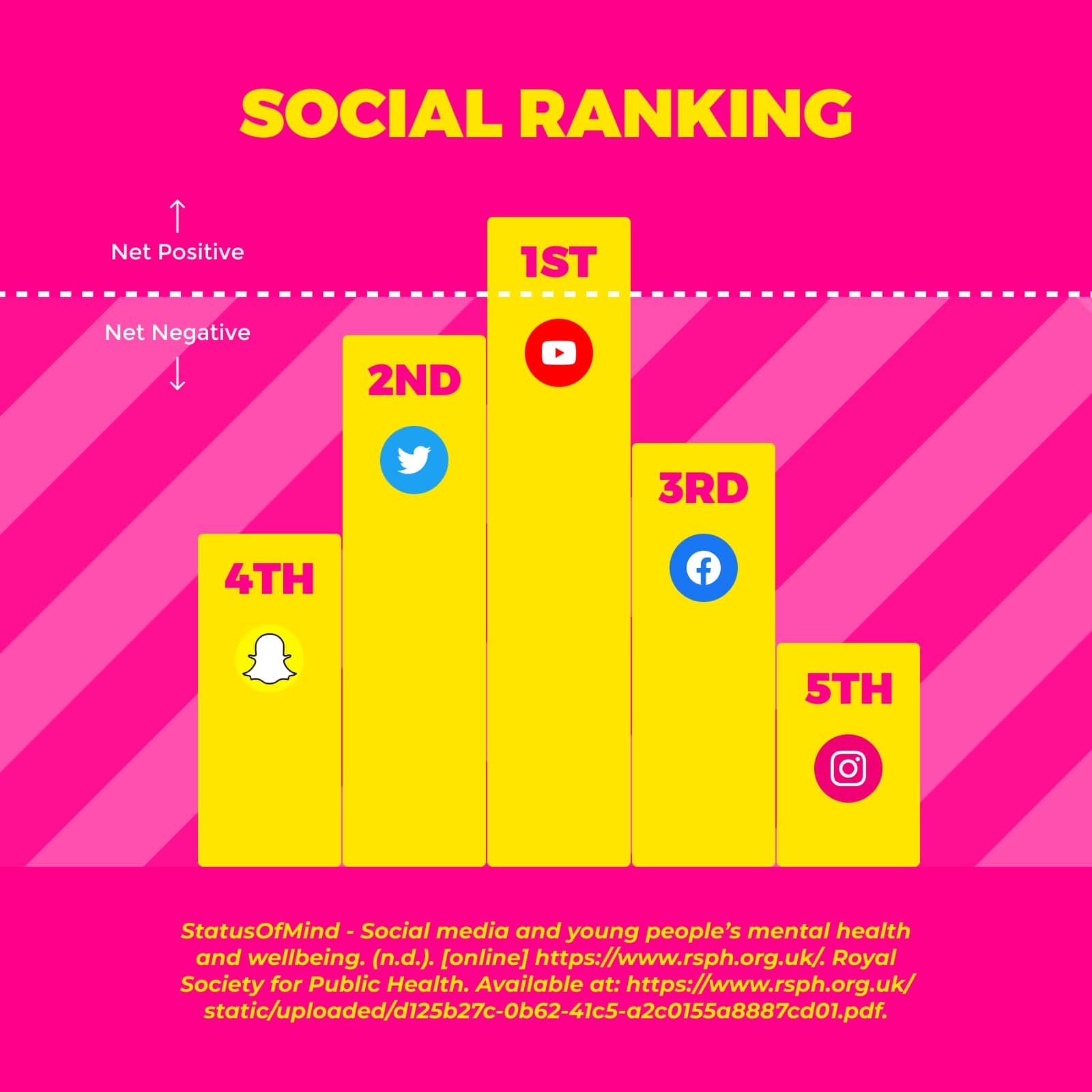

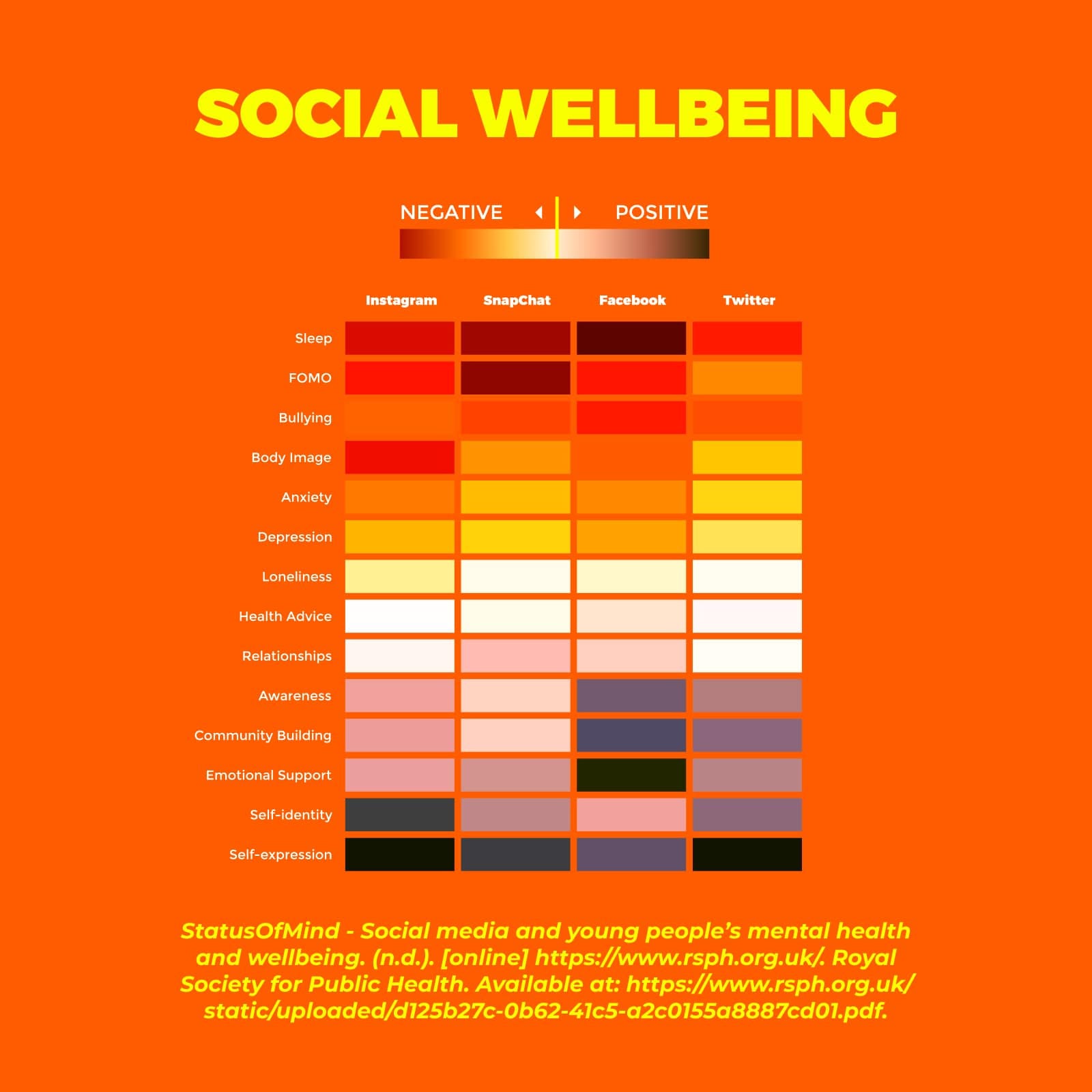

Which platform designs contribute most to mental health risks?

When it comes to young people’s health and wellbeing, research shows that the most harmful platforms tend to be Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Facebook, and Twitter. Across the scientific literature, one design pattern stands out as a common driver of harm: the feed. Ironically, the very component designed to keep users engaged may be the one doing the most damage.

The feed is a near-universal design pattern, appearing across almost every major platform, including Twitter (and its derivatives like BlueSky, Mastodon, and Threads), Facebook, Medium, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, TikTok, Tinder, SnapChat, and Reddit.

The social feed contains cards algorithmically placed in either a grid or list format with pagination. For either mobile or web, a card can contain short form text, images, GIFs or videos. Also a profile page is included for showcasing social status through a follower count.

Why do social platforms insist on using the feed?

Because it works. The feed keeps users engaged and engagement keeps the business alive.

If users get bored, they leave. And with so many lookalike competitors, platforms can’t afford to lose attention. The feed becomes the digital town square, filled with gossip, trends, and status games, designed to feel like you can’t look away.

Behind the scenes, the business goal is clear: maximize revenue. The key metric? Customer Lifetime Value (CLV)—a measure of how long a user stays on the platform and how much value they generate over time, whether through spending or the data they give up to advertisers.

How does the feed keep people hooked?

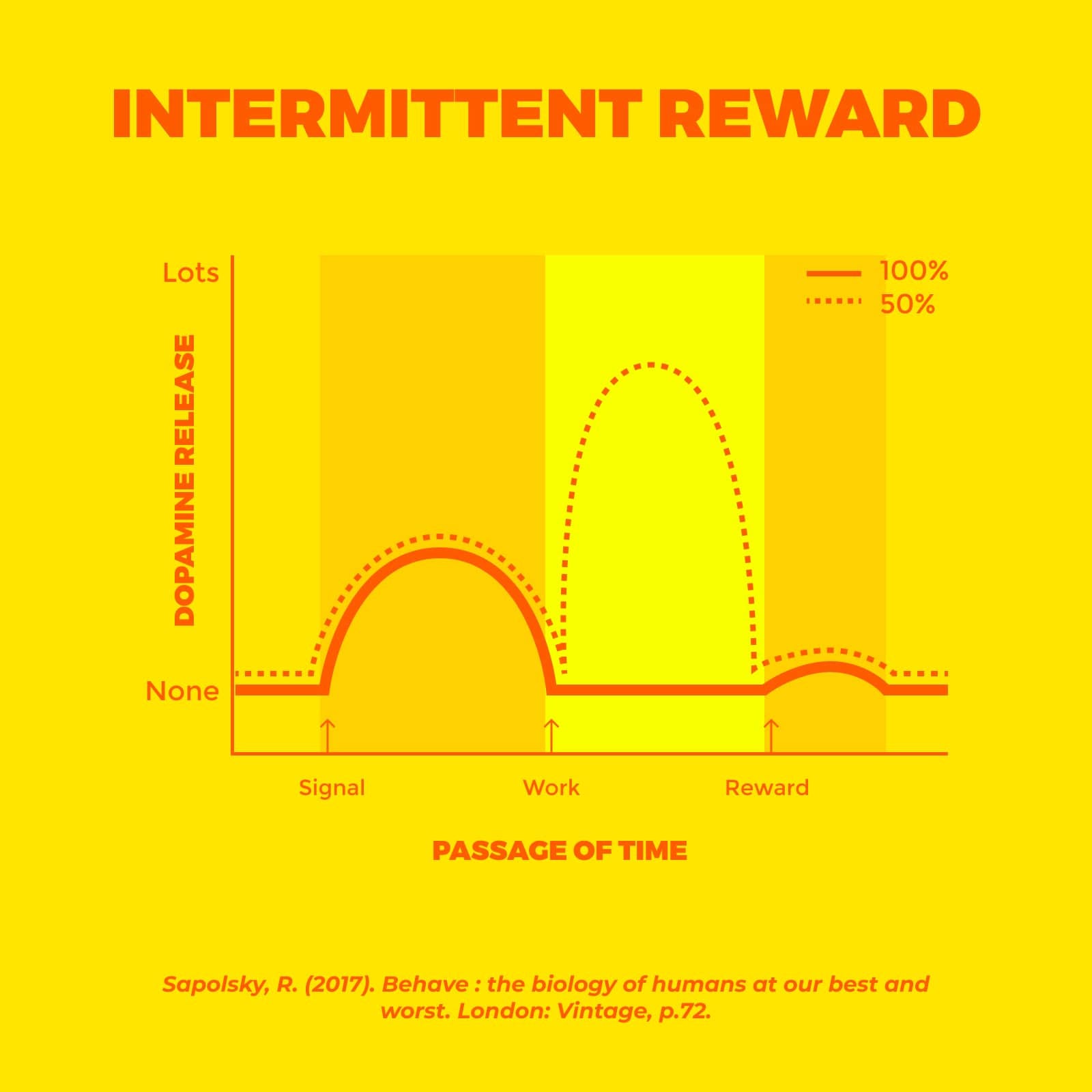

It uses the psychology of variable rewards, the same principle behind slot machines and other forms of gambling. You scroll. You swipe. You refresh. Most of the time, it’s boring—but every so often, something exciting shows up. That unpredictability triggers your dopamine system.

Dopamine isn’t about the reward itself—it’s about anticipation. The molecule motivates you to seek novelty, not just enjoy it. So you don’t scroll because you found something great. You scroll because you might.

That mix of randomness and reward creates a cycle that’s hard to break. The feed becomes a bottomless slot machine of content—occasionally delightful, often draining, always demanding your attention.

If we want healthier digital spaces, we need to rethink systems that exploit our biology—and start designing ones that respect it.

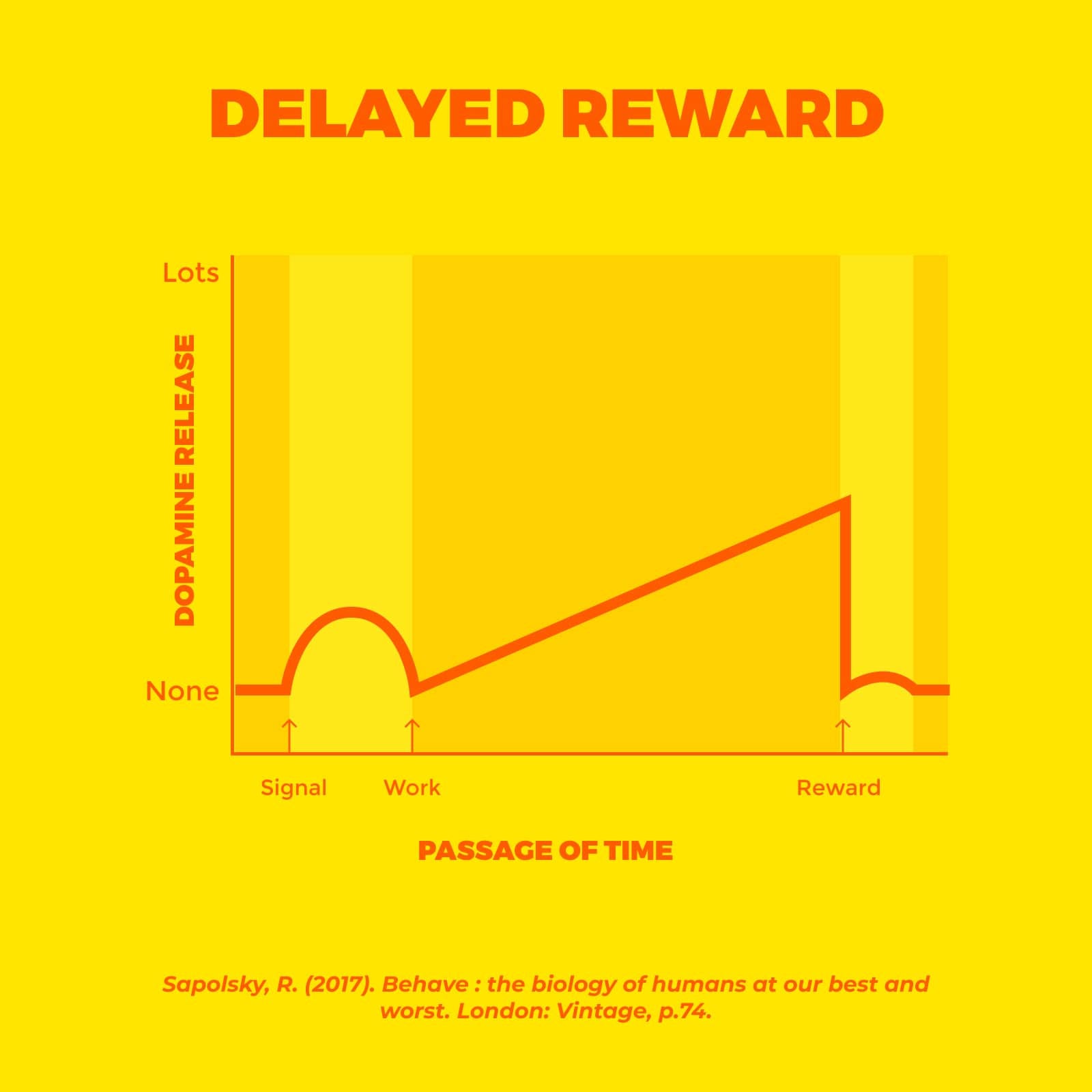

Novelty keeps us engaged, but not always in healthy ways. It often shows up as outrage, extreme opinions, social validation through likes, or envy from constant comparisons of wealth, beauty, or status.

These illusive patterns nudge us toward instant gratification, pulling us away from something far more meaningful: the deeper satisfaction that comes from delayed rewards. It’s in the waiting, the striving, the building over time, where real fulfillment lives.

Who are the most vulnerable?

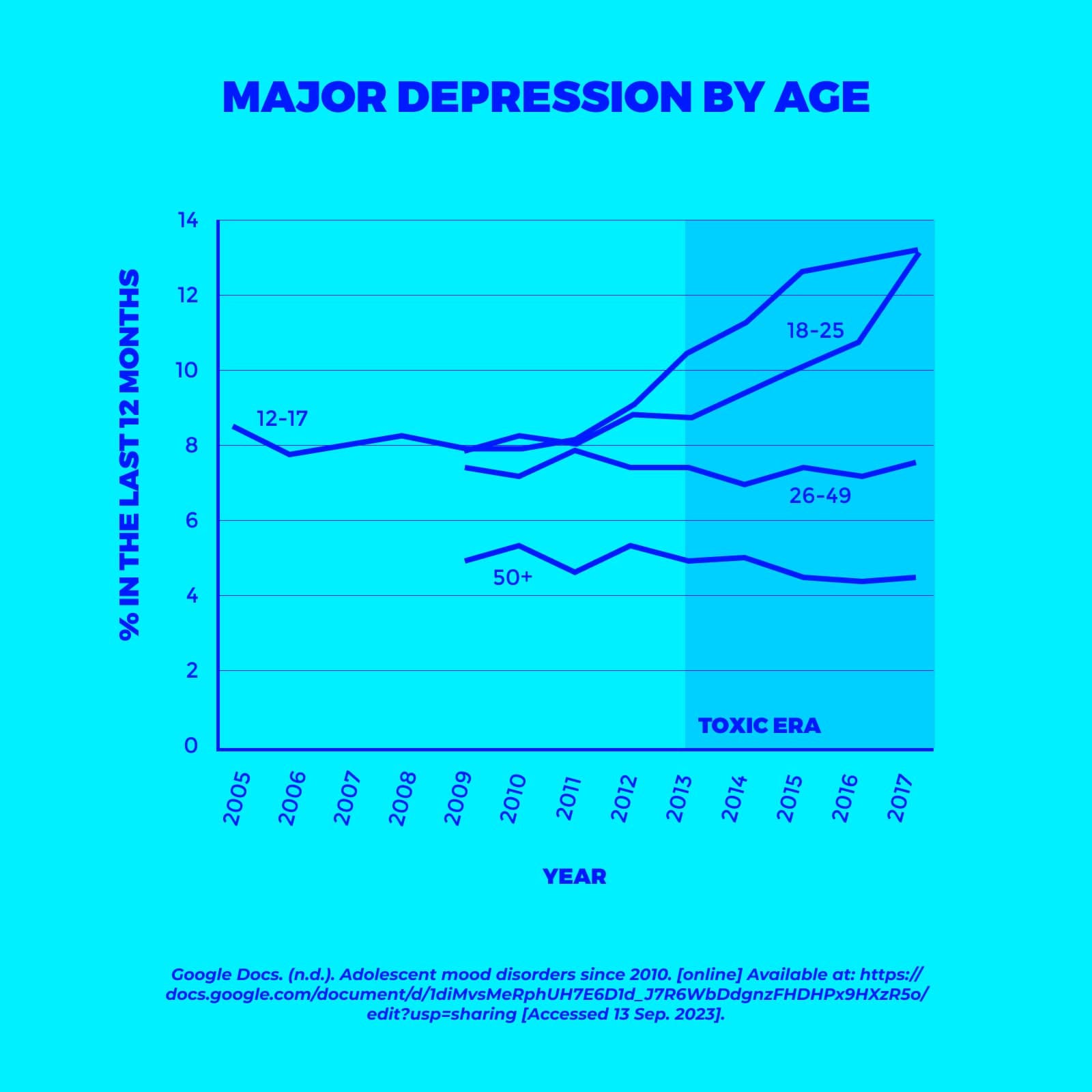

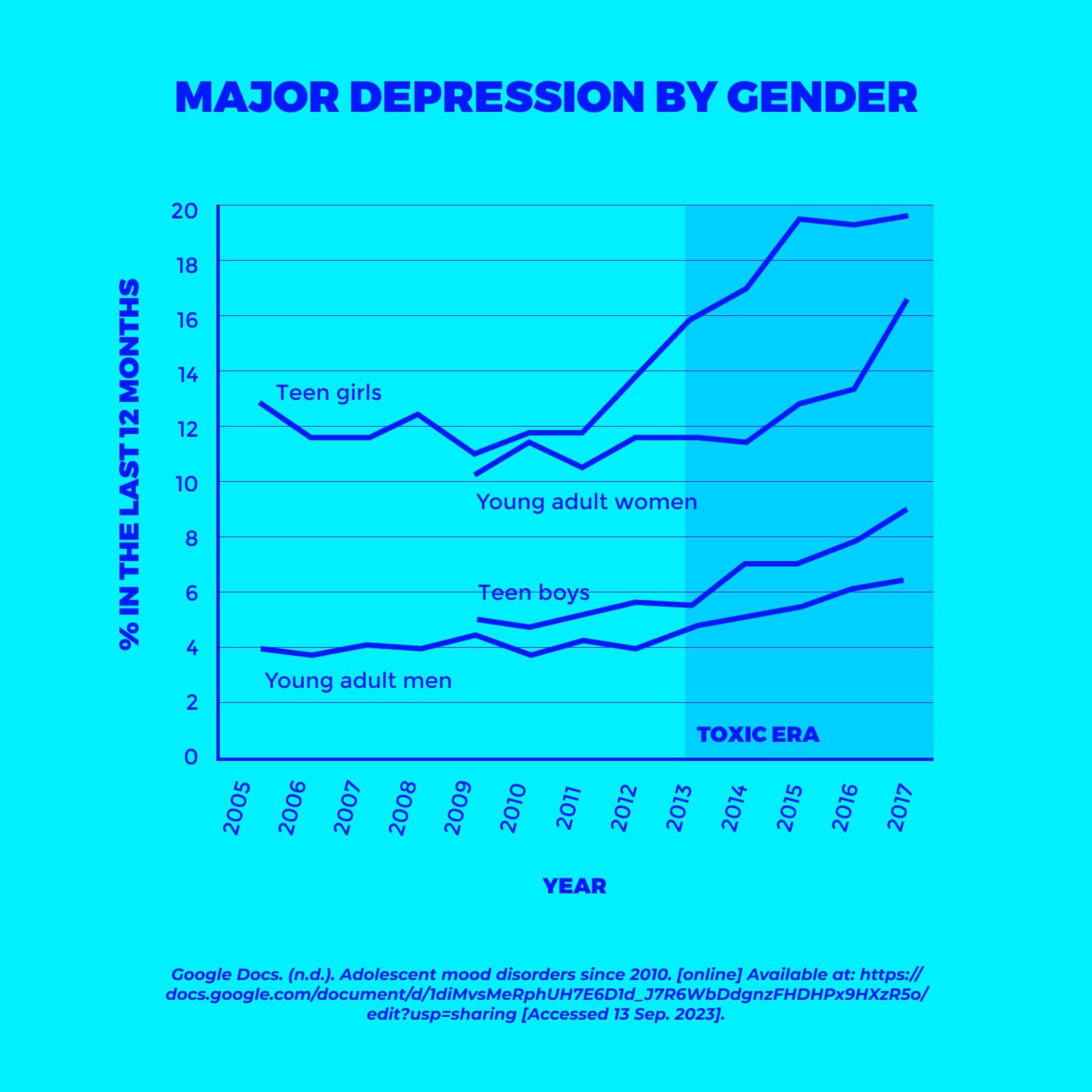

Using data based on major depression from the USA since the inception of social media, those who tend to be affected are:

- Gen Z is most affected, having grown up with social media during critical years of brain development—when identity, self-worth, and emotional regulation are still forming.

- Millennials are also impacted, though to a lesser extent, having experienced both life before and after social media’s rise.

- Women and girls are disproportionately affected, as they tend to spend more time on social platforms and are more exposed to appearance-based comparisons and social feedback loops.

Age verification remains dangerously inadequate across platforms. Despite internal research, highlighted by whistleblowers like Frances Haugen, companies have knowingly allowed children under 13 to access their apps. And the younger the user, the more vulnerable they are to illusive design patterns that exploit their still-developing brains.

How does social media feed mental illness?

There are 16 effects that are caused by the interaction design of the social feed based on the conducted research that you can find in the Notes section at the end of this article. Each effect is grouped using an altruheuristic created to highlight unethical interactions. More information about my altruheuristics framework can be found here. Bare in mind that all these effects can eventually lead to anxiety and depression.

- Anxiety & Depression

– General anxiety & depression leading to cognitive distortions, fear, bias exploitation and self-harm. - Comparison

– Comparison of self-image leading to low self-esteem.

– Curated highlight reels.

– Unhealthy levels of perfectionism with self.

– Body image obsession leading to eating disorders & plastic surgery.

– Polarization and filter bubbles.

– Self identity modification. - Exclusion

– Fear of missing out, being excluded and feelings of loneliness.

– Bullying and trolling. - Dopamine Regulation

– Sleep deprivation from overstimulation.

– Addiction to novelty seeking.

– Context switching leading to a lack of sustained focus. - Status Play

– Social status exploitation leading to emotional dysregulation. - Truth

– Reality distortion from algorithmic bias.

– Misinformation and disinformation.

– Divisiveness through the use of bots.

Dissecting the illusive social feed

The social feed is more than a collection of posts, it is a system of interconnected parts that together shape our mental and emotional landscape. While visible design patterns set the stage, hidden algorithms work in the background, determining what rises to the surface, when it appears, and how we are guided to react.

These systems do more than sort content. They influence behaviour, often pairing engagement-driven algorithms with persuasive design patterns that prioritize attention over wellbeing. The outcome is not the fault of any single user, but of a structure optimized for growth at the expense of balance.

To build healthier digital environments, we must first understand how these mechanisms affect us. The following nine design patterns illustrate the ways current systems contribute to mental health challenges, and where more ethical alternatives could emerge.

1. Profile card

Altruheuristics

- Anxiety & Depression

– General anxiety & depression leading to cognitive distortions, fear, bias exploitation and self-harm. - Comparison

– Comparison of self-image leading to low self-esteem.

– Curated highlight reels.

– Unhealthy levels of perfectionism with self.

– Body image obsession leading to eating disorders & plastic surgery.

– Polarization and filter bubbles.

– Self identity modification. - Status Play

– Social status exploitation leading to emotional dysregulation.

The profile card is a subtle yet powerful status signal. Elements like follower counts and bios are designed to communicate trust, authority, and social worth.

But the very concept of “following” breaks from how relationships work in real life. We don’t trail behind others like sheep; we engage, exchange, and connect. The binary of follower/following reduces complex human relationships to numbers and hierarchy.

Follower counts tap into our bias toward perceived authority—bigger numbers imply credibility. But that’s a shortcut, not a signal of actual expertise or value.

Platforms like Twitter amplify this effect by rewarding provocative content with greater reach. Users learn that outrage and divisiveness drive engagement, and in turn, attention. This leads to a cycle: bold posts attract reactive followers, which reinforce the behaviour, fueling the mob mentality we see in online pile-ons and cancel culture.

At the other end, low follower counts can unfairly signal low status, even if the account is new, niche, or simply not gaming the algorithm. Meanwhile, accounts with thousands of followers and zero following send an entirely different message: high status without reciprocation, often interpreted as exclusivity or superiority.

To break these toxic cycles, we need to question the values our interfaces reward and design for authenticity over authority.

The comparison between our follower count and theirs often triggers emotional responses—especially when the numbers aren’t in our favor. A lower count can make us feel less valued, less seen, or even invisible. A higher count can boost our sense of worth. But because content from large accounts dominates the feed, most of our comparisons trend downward—making us feel smaller, less relevant, and left behind.

But here’s the problem: the follower count is an illusion of authority. It’s not always real and it may not even be earned.

Many inflate their numbers through third-party services and follower farms, where one payment can buy thousands of fake followers. These accounts may look important at a glance, but often show little real engagement, revealing the gap between appearance and influence.

Others engage in the “follow-for-follow” game, a quiet, transactional exchange that can later turn sour when one side unfollows. In close relationships, this unspoken contract can have real emotional weight. Unfollowing, unfriending, or unmatching a friend or family member isn’t just a click, it can be perceived as rejection.

And then there are bots—millions of them. These artificial accounts can simulate engagement, boost status, spread misinformation, and even manipulate public opinion. Reports suggest bots and inactive users may account for nearly 1 in 5 online interactions, creating a warped perception of popularity and community.

In short, the numbers we see—and compare ourselves to—are often smoke and mirrors. When we can’t distinguish between real people and artificial ones, our sense of value and belonging becomes distorted.

A quick summary of some of Musk’s follower data for those who haven’t read the more detailed report: Just over 42 percent of Musk’s more than 153 million followers have 0 followers. More than 40 percent have zero tweets posted on their account. Around 40 percent of Musk’s followers also follow less than 10 users. This points to a few things. Many of these accounts can be fake accounts or bots. Also, many of these accounts can simply belong to inactive users or people who set up an account and rarely if ever return.

When followers are bots or inactive, low engagement can trigger self-doubt. We start tying our worth to a number, questioning ourselves over a lost follower, when it was likely just a bot.

This obsession distorts our view. The follower count becomes a status symbol, hiding the humanity behind the numbers. We stop seeing people as people and start seeing them as metrics. And in doing so, we lose compassion, for others, and for ourselves.

2. Messages, comments and replies

Altruheuristics

- Exclusion

– Fear of missing out, being excluded and feelings of loneliness.

– Bullying and trolling.

An honorable mention: All social apps include messaging or comment features—separate from the feed, but potentially just as toxic. These are breeding grounds for bullying, spam, and harassment, especially on platforms that allow anonymity or pseudonyms.

Apps like Reddit let users hide behind new identities. This fuels the online disinhibition effect, where actions feel detached from real-world consequences. Like wearing an invisibility cloak, it invites the question: what would you do if no one could see you?

Anonymity can erode empathy. Without names, faces, or tone, even harmless messages can feel hostile. And when comment visibility is manipulated, via votes or verification badges, users outside the inner circle are quietly excluded.

3. Upvoting

Altruheuristics

- Truth

– Reality distortion from algorithmic bias.

– Misinformation and disinformation.

– Divisiveness through the use of bots.

The upvote/downvote system, a staple since the early forum days, is meant to mimic democracy, giving every post a fair shot at visibility. But in practice, it’s often exploited for social validation, leading to feelings of rejection and a warped sense of reality.

Platforms like Reddit and Product Hunt default to showing the most upvoted content, making it seem like virality is normal. In truth, most posts die in obscurity. If you sort by “new,” the gap becomes clear, and the illusion shatters.

Voting can be manipulated by herd behavior, where early engagement gives certain posts an unfair boost to the front page, regardless of quality. Others get downvoted for reasons that have nothing to do with merit.

Timing matters, too. When most users are asleep, say, in the US—posts can go unnoticed. Midnight server resets create brief windows of visibility that unfairly favor those who post at just the right moment.

Creators often compete with others who have massive followings, making it harder for their work to be seen. Moderators can remove posts without warning, even for something as minor as a duplicate.

These systems aren’t democratic. They’re opaque, easy to game, and quietly distort how we think and what we see. If we want to build healthier digital spaces, we need tools that earn trust through transparency, fairness, and human-centered design.

4. Pagination

Altruheuristics

- Anxiety & Depression

– General anxiety & depression leading to cognitive distortions, fear, bias exploitation and self-harm. - Dopamine Regulation

– Sleep deprivation from overstimulation.

– Addiction to novelty seeking.

– Context switching leading to a lack of sustained focus.

TikTok auto-plays the next video, YouTube uses countdowns, and Tinder keeps you swiping, all designed to keep us engaged without pause. There’s no natural stopping point, just a loop of constant stimulation.

Behind this are recommender systems, using our history, our friends’ choices, and trending data to predict what we’ll watch next, all to maximize engagement.

But these interactions often create a relentless pursuit of dopamine, leaving us overstimulated and emotionally drained. Over time, this can contribute to rising anxiety, depression, and burnout.

Rapid context switching, from short videos to tweets to memes, fragments our attention. It makes deep focus harder and can even mimic symptoms of ADHD.

5. Reactions

Altruheuristics

- Dopamine Regulation

– Sleep deprivation from overstimulation.

– Addiction to novelty seeking.

– Context switching leading to a lack of sustained focus. - Status Play

– Social status exploitation leading to emotional dysregulation.

Few social features have shaped our online interactions as much as the Facebook Like button. That little hit of dopamine from a like, reaction, favorite, clap, or match can lift our social confidence.

Likes offer a powerful sense of validation. But when they’re missing, it can distort how we see ourselves, triggering feelings of rejection and emotional imbalance.

This design, much like a voting system, can be manipulated—and yet it’s fully controlled by opaque algorithms. Your content reach might shrink due to factors like shadow-banning, verified user preferences, or arbitrary decisions. Even reactions can be faked by bots.

We naturally crave validation, but tying our self-worth to these engineered signals controlled by impersonal algorithms isn’t healthy. The problem lies in the system, not in us.

6. Notifications

Altruheuristics

- Exclusion

– Fear of missing out, being excluded and feelings of loneliness.

– Bullying and trolling. - Dopamine Regulation

– Sleep deprivation from overstimulation.

– Addiction to novelty seeking.

– Context switching leading to a lack of sustained focus.

In-app notifications, like reactions, use a red dot to signal social interactions such as follows, replies, or reactions, creating intermittent reinforcement. This triggers a dopamine boost, but when the dot disappears, it can feel like social rejection, leading to distorted thinking.

Our brains crave these hits, the refresh of a page acts like pulling a lever or spinning a roulette wheel, building anticipation and encouraging repeated checking. Yet, the absence of a notification doesn’t mean rejection; often, there are many harmless reasons behind it.

These intermittent rewards keep us engaged, driven by metrics like customer lifetime value. But this social validation is often an illusion. By becoming aware of this, we can consciously reduce our exposure and create healthier habits.

7. Short-form Content Cards

Altruheuristics

- Anxiety & Depression

– General anxiety & depression leading to cognitive distortions, fear, bias exploitation and self-harm. - Comparison

– Comparison of self-image leading to low self-esteem.

– Curated highlight reels.

– Unhealthy levels of perfectionism with self.

– Body image obsession leading to eating disorders & plastic surgery.

– Polarization and filter bubbles.

– Self identity modification. - Exclusion

– Fear of missing out, being excluded and feelings of loneliness.

– Bullying and trolling. - Dopamine Regulation

– Sleep deprivation from overstimulation.

– Addiction to novelty seeking.

– Context switching leading to a lack of sustained focus. - Status Play

– Social status exploitation leading to emotional dysregulation. - Truth

– Reality distortion from algorithmic bias.

– Misinformation and disinformation.

– Divisiveness through the use of bots.

Endless short-form content, whether text, images, or videos that auto-paginates encourages impulsive switching, pulling our focus from meaningful, deep work to quick dopamine hits. This addictive pattern makes it hard to find sustained purpose.

Formats like tweets or TikTok clips often strip away context, leading us to jump to conclusions and reinforcing cognitive distortions. Over time, this can fuel anxiety and warp our view of the world. It also feeds our endless craving for more.

Take YouTube thumbnails designed to get clicks, they often show surprised faces because novelty triggers dopamine, tapping into our brain’s primitive drive for newness.

Character limits and short durations push creators to focus on highlights, often clickbait, where outrage grabs attention. As users get used to outrage, more is needed to keep them engaged. Like breaking news headlines, space is limited, so the most triggering words win.

For example, violent crime stories usually paint killers as cold and calculated but omit the mental health struggles behind the acts. It’s too complex for a headline and less likely to grab attention. This one-sided narrative keeps us stuck in learned helplessness with a skewed worldview. Constant breaking news plays on our availability bias, making violence feel constant and everywhere.

Choosing to limit our exposure is a powerful step toward protecting our well-being and regaining control.

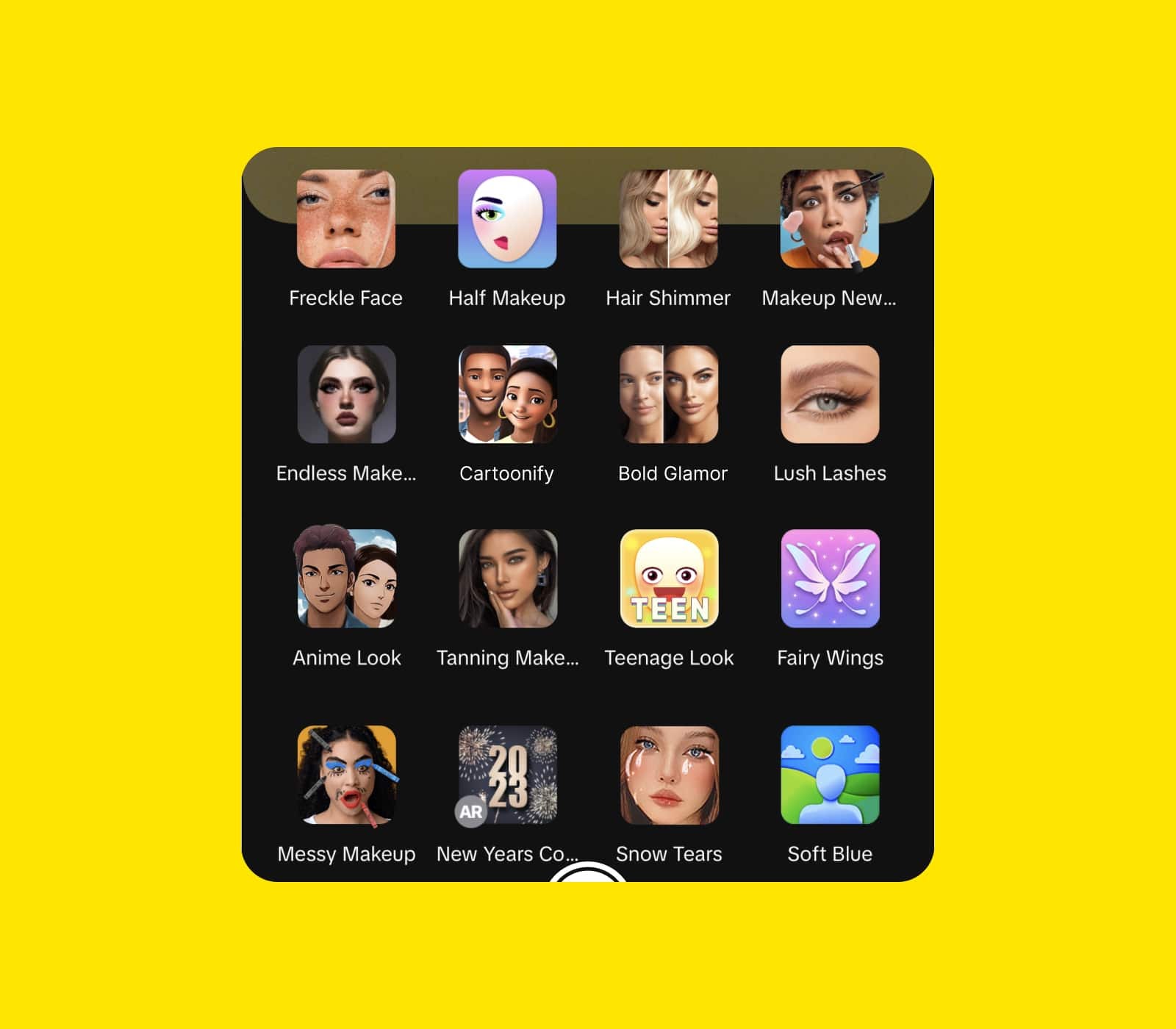

8. AI Filtered Cards

Altruheuristics

- Anxiety & Depression

– General anxiety & depression leading to cognitive distortions, fear, bias exploitation and self-harm. - Comparison

– Comparison of self-image leading to low self-esteem.

– Curated highlight reels.

– Unhealthy levels of perfectionism with self.

– Body image obsession leading to eating disorders & plastic surgery.

– Polarization and filter bubbles.

– Self identity modification. - Status Play

– Social status exploitation leading to emotional dysregulation. - Truth

– Reality distortion from algorithmic bias.

– Misinformation and disinformation.

– Divisiveness through the use of bots.

Many social platforms let users apply beauty filters to photos and videos without any disclaimers, drastically altering faces and bodies. Spots disappear, eyes grow larger, noses shrink, amplifying unrealistic beauty ideals set by celebrities and influencers.

Upward comparison steals joy by lowering our sense of social worth, making us self-conscious, anxious, and sometimes depressed. Like curated highlight reels, feeds show a filtered reality we measure against our true, unfiltered selves.

These filters impact women more, creating impossible standards that erode self-esteem over time. They are an unregulated social experiment targeting the most vulnerable. This cycle of comparison is a leading cause of anxiety, depression, and suicide. The strongest path forward is to recognize the system’s role and choose mindful abstention.

9. Algorithmic Cards

Altruheuristics

- Anxiety & Depression

– General anxiety & depression leading to cognitive distortions, fear, bias exploitation and self-harm. - Comparison

– Comparison of self-image leading to low self-esteem.

– Curated highlight reels.

– Unhealthy levels of perfectionism with self.

– Body image obsession leading to eating disorders & plastic surgery.

– Polarization and filter bubbles.

– Self identity modification. - Exclusion

– Fear of missing out, being excluded and feelings of loneliness.

– Bullying and trolling. - Dopamine Regulation

– Sleep deprivation from overstimulation.

– Addiction to novelty seeking.

– Context switching leading to a lack of sustained focus. - Status Play

– Social status exploitation leading to emotional dysregulation. - Truth

– Reality distortion from algorithmic bias.

– Misinformation and disinformation.

– Divisiveness through the use of bots.

The most hidden form of design is often the most powerful. The feed algorithm, invisible yet influential, concentrates much of the harm we face. Originally, feeds were chronological, but engagement couldn’t compete with AI-driven ranking systems.

These algorithms shape our reality, often triggering cognitive distortions that pull us away from well-being.

They learn our habits through clicks, watch time, and subscriptions, fueling addiction by reinforcing confirmation bias and creating echo chambers. Whether it’s YouTube recommendations or TikTok videos, these systems can be manipulated through keyword bidding and hashtags.

Content that fails to engage is pushed aside, while curated “survivors” dominate, overnight celebrities, models, and influencers who benefit from rare genetics, intense effort, and behind-the-scenes production, creating a misleading image of effortless success.

Bots stir engagement with provocation, and the algorithm cannot distinguish real from fake news. Our well-being shouldn’t depend on a system indifferent to our values and boundaries.

It amplifies friends’ highlights, often sparking feelings of social rejection and missing out.

And when voices challenge the gatekeepers, they risk soft or hard shadow bans without notice. The algorithm values customer lifetime revenue over genuine well-being.

Unfortunately, e-commerce companies lobbied successfully to have the age of “internet adulthood” set instead at 13. Now, more than two decades later, today’s 13-year-olds are not doing well. Federal law is outdated and inadequate. The age should be raised. More power should be given to parents, less to companies. — Jonathan Haidt

Suggested Design Solutions

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Scientists have put forward solutions to address the hidden harms of social feed design including:

- The introduction of a pop-up heavy usage warning on social media

- Social media platforms to highlight when photos of people have been digitally manipulated

- Social media platforms to identify users who could be suffering from mental health problems by their posts and other data, and discreetly signpost to support

- Don’t promote unrealistic beauty standards

- Encourage positive self-affirmations

- Acknowledge and address mental health risks

- Congress should pass legislation compelling Facebook, Instagram, and all other social-media platforms to allow academic researchers access to their data. One such bill is the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, proposed by the Stanford University researcher Nate Persily.

- Congress should toughen the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. An early version of the legislation proposed 16 as the age at which children should legally be allowed to give away their data and their privacy. Unfortunately, e-commerce companies lobbied successfully to have the age of “internet adulthood” set instead at 13. Now, more than two decades later, today’s 13-year-olds are not doing well. Federal law is outdated and inadequate. The age should be raised. More power should be given to parents, less to companies.

- Elevate user safety, health, and wellbeing in the culture and leadership of technology companies.

- Assess and address risks to users at the front end of product development.

- Continually measure the impact of products on user health and wellbeing and share data with the public.

- Recognize that the impact of platforms and products can vary from user to user, and proactively ensure that products designed for adults are also safe for children and adolescents.

- Allow users to provide informative data about their online experience to independent researchers.

- Directly provide researchers with data to enable understanding of (a) subgroups of users most at risk of harm and (b) algorithmic design and operation.

- Partner with researchers and experts to analyze the mental health impacts of new products and features in advance of rollout. Regularly publish findings.

- Allow a broad range of researchers to access data and previous research instead of providing data access to a privileged few.

- Take a holistic approach to designing online spaces hospitable to young people.

- Limit children’s exposure to harmful online content.

- Give users opportunities to control their online activity, including by opting out of content they may find harmful.

- Develop products that actively safeguard and promote mental health and wellbeing.

- Promote equitable access to technology that supports the wellbeing of children and youth.

- Co-create a code of ethics. First, visual modifications must be clearly labelled, so that consumers can easily distinguish real features from those that have been augmented. And second, as with risks associated with any sort of product, brands should explicitly specify the potentially harmful effects of their products on users’ psychological wellbeing.

My Solution

I created the Altruheuristics framework to complement NNGroup’s Heuristic Evaluation Workbook. It helps design teams, especially those with low UX maturity to uncover unethical patterns that traditional principles often miss, using insights from biology and CBT. You can evaluate unethical interactions early, at wireframes, flows, prototypes, or mockups. The sooner, the better. Get the free guide here.

Takeaways

It’s clear that limited collaboration with researchers lets social platforms hide the true impact they have. Regulations are emerging to slow the harm, but much damage may already be done. Setting the internet adulthood age at 13 lets these platforms target the most vulnerable and this must change. Research often uses a broad definition of social media, making it hard to pinpoint real problem areas and sometimes leading to misleading conclusions. Together, these hidden factors in our feeds create chronic overstimulation, and it’s up to us as design leaders to create better systems that protect well-being.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts — Aristotle.

One surprising insight from my research is that dopamine depletion wasn’t mentioned. Yet we know dopamine loss reduces pleasure and increases pain. These products initially feel rewarding, but the real risk is when short-term pleasure turns into chronic imbalance. That constant overstimulation often leads to anxiety and depression, a consequence we must recognize and address.

At first glance, it might seem like design alone is to blame. But evidence shows that every harmful interaction is shaped by deeper systems, through backend business logic, automated decisions, and algorithmic amplification. Design becomes the bridge between these invisible systems and human experience. That bridge can either transmit harm or be rebuilt to support wellbeing.

When the user experience is controlled by an algorithm incapable of experiencing empathy, we end up with apathy driving the user experience and not compassion.

Empathy is often considered a human trait, yet today many of our experiences are shaped by algorithms that lack it entirely. Without care or context, these systems default to indifference, replacing compassion with apathy. This is not inevitable. It is a reminder that we have the power, and the responsibility to embed human values into the tools we create.

As design leaders, we strive to create with empathy, but often lack the power to influence decisions. It’s time for our community to speak up against the misuse of our craft. Even leading UX organizations like NNGroup and W3C overlook the risks of social media. Finding your voice without authority takes real courage.

Scientists still struggle to determine if social media causes mental illness or if those struggling turn to it more. This cycle seems self-reinforcing, but several findings suggest social media plays a significant role.

- Sometimes comparing ourselves with others, short-term stress, and short dopamine bursts can be good. Chronic exposure to these effects however can be detrimental over time.

- Those who abstain or significantly reduce their expose to social media show a large improvement in their wellbeing.

- Social platforms are intentionally designed for chronic stimulation. Like gambling in casinos, removing windows, using bright lights and colors are all part of the experience.

Thank you for reading. If this article brought you value, please share it so others can benefit too. It’s our moral responsibility to create products that protect and empower young minds.

To learn more about how we’re redesigning tools for clearer thinking, deeper connection, and better habits, visit circlo.com. Build a healthier inner world with science-based tools that help you reframe, reflect, and grow.

Notes

The evidence presented here isn’t exhaustive however it illustrates the common patterns I’ve found when mapping the social feed to mental illness.

- The first is that social media presents “curated” versions of lives, and girls may be more adversely affected than boys by the gap between appearance and reality. Many have observed that for girls, more than for boys, social life revolves around inclusion and exclusion. Social media vastly increases the frequency with which teenagers see people they know having fun and doing things together-including things to which they themselves were not invited. While this can increase FOMO (fear of missing out), which affects both boys and girls, scrolling through hundreds of such photos, girls may be more pained than boys by what Georgetown University linguistics professor Deborah Tannen calls “FOBLO” — fear of being left out? When a girl sees images of her friends doing something she was invited to do but couldn’t attend (missed out), it produces a different psychological effect than when she is intentionally not invited (left out). And as Twenge reports, “Girls use social media more often, giving them additional opportunities to feel excluded and lonely when they see their friends or classmates getting together without them.” The number of teens of all ages who feel left out, whether boys or girls, is at an all-time high, according to Twenge, but the increase has been larger for girls. From 2010 to 2015, the percentage of teen boys who said they often felt left out increased from 21 to 27. For girls, the percentage jumped from 27 to 40. Another consequence of social media curation is that girls are bombarded with images of girls and women whose beauty is artificially enhanced, making girls ever more insecure about their own appearance. It’s not just fashion models whose images are altered nowadays; platforms such as Snapchat and instagram provide “filters” that girls use to enhance the selfies they pose for and edit, so even their friends now seem to be more beautiful. These filters make noses smaller, lips bigger, and skin smoother.” This has led to a new phenomenon: some young women now want plastic surgery to make themselves look like they do in their enhanced selfies.

- Given the breadth of correlational research linking social media use to worse well-being, we undertook an experimental study to investigate the potential causal role that social media plays in this relationship. METHODS: After a week of baseline monitoring, 143 undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania were randomly assigned to either limit Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat use to 10 minutes, per platform, per day, or to use social media as usual for three weeks. RESULTS: The limited use group showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks compared to the control group. Both groups showed significant decreases in anxiety and fear of missing out over baseline, suggesting a benefit of increased self-monitoring.

- Few people realize it, but a chilling 19 percent of interactions on social media are already between humans and bots, not humans and humans. Studies based on statistical modeling of social media networks have found that these bots only need to represent 5 to 10 percent of the participants in a discussion to manipulate public opinion in their favor, making their view the dominant one, held by more than two-thirds of all participants. When those on the powerful fringe — the Mrs. Salts of the world -enforce a position that doesn’t reflect reality, join together with general ignorance, or harness the silent support of all those waiting around to see which way the wind will blow, they can rapidly solidify into a distorted, hurricane-strength social force. wielding the influence of a majority with the true support of a meager few, the resulting collective illusion harnesses crowd power to entrap us in a dangerous spiral of silence.

- Research suggests that young people who are heavy users of social media — spending more than two hours per day on social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter or Instagram — are more likely to report poor mental health, including psychological distress (symptoms of anxiety and depression). Seeing friends constantly on holiday or enjoying nights out can make young people feel like they are missing out while others enjoy life. These feelings can promote a ‘compare and despair’ attitude in young people. Individuals may view heavily photoshopped — don’t hypenate, edited or staged photographs and videos and compare them to their seemingly mundane lives. The findings of a small study, commissioned by Anxiety UK, supported this idea and found evidence of social media feeding anxiety and increasing feelings of inadequacy. The unrealistic expectations set by social media may leave young people with feelings of self-consciousness, low self-esteem and the pursuit of perfectionism which can manifest as anxiety disorders. Use of social media, particularly operating more than one social media account simultaneously, has also been shown to be linked with symptoms of social anxiety.

- The sharing of photos and videos on social media means that young people are experiencing a practically endless stream of others’ experiences that can potentially fuel feelings that they are missing out on life — whilst others enjoy theirs — and that has been described as a ‘highlight reel’ of friends’ lives. FoMO has been robustly linked to higher levels of social media engagement, meaning that the more an individual uses social media, the more likely they are to experience FoMO.

- AR overlays are often used to alter a consumer’s appearance. This may seem harmless enough, but physical appearance is a key component of identity and as such it can have a substantial impact on psychological well-being. Studies have shown that virtually modifying appearance can provoke anxiety, body dysmorphia, and sometimes even motivate people to seek cosmetic surgery.

- On the other hand, for the participants who were already happy with their appearances, seeing their faces with realistic modifications made them feel less certain about their natural looks, shaking their typical self-confidence. In a follow-up survey, we found that when the AR filter increased the gap between how participants wanted to look and how they felt they actually looked, it reduced their self-compassion and tolerance for their own physical flaws.

- The crisis is not a result of changes in the willingness of young people to self-diagnose, nor in the willingness of clinicians to expand terms or over-diagnose. We know this because the same trends occurred, at the same time, and in roughly the same magnitudes, in behavioral manifestations of depression and anxiety, including hospital admissions for self-harm, and completed **suicides…**how sharp and sudden the increase has been for hospital admissions for teen girls who had intentionally harmed themselves, mostly by cutting themselves.

- The correlation of childhood lead exposure and adult IQ is r = .11, which is enough to justify a national campaign to remove lead from water supplies. These correlations are smaller than the links between mood disorders and social media use for girls. Gotz et al. note that such putatively “small” effects can have a very large impact on public health when we are examining “effects that accumulate over time and at scale”, such as millions of teens spending 20 hours per week, every week for many years, trying to perfect their Instagram profiles while scrolling through the even-more perfect profiles of other teens.

- Teens often say that they enjoy social media while they are using it — which is something heroin users are likely to say too. The more important question is whether the teens themselves think that social media is, overall, good for their mental health. The answer is consistently “no.” Facebook’s own internal research, brought out by Frances Haugen in the Wall Street Journal, concluded that “Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression … This reaction was unprompted and consistent across all groups.”

- In particular, YouTube was highlighted as a “rabbit hole”, with the seemingly infinite stream of content enabling people to watch one video after another without making a conscious decision to do so. YouTube’s Marketing Director, Rich Waterworth, confirmed to us that around 70% of the time people spend on YouTube is spent watching videos that have been ‘recommended’ to them by the platform’s algorithms, rather than content they have actively searched for.

- The effects of engagement metrics sit alongside the fact that platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram use augmented reality technologies to provide users with image-enhancing filters that can be applied to photos before they are shared. There are concerns that ‘beautifying’ filters can have a potentially negative impact on self-esteem, and Instagram was ranked worst by young people surveyed by the Royal Society of Public Health for its effect on body image. These filters allow users to make their lips appear fuller, hips rounder or waist narrower in order to conform to others’ pre-conceived ideas of physical beauty. It is also argued that this can lead to body dysmorphic disorder, with cosmetic surgeons reporting that patients are increasingly bringing ‘filtered’ pictures of themselves to consultations, despite such images being unobtainable using surgical procedures. Vishal Shah told us that the company takes the issue of body dysmorphia “seriously”.

- In the digital economy, data, design and monetization are inextricably tied. The 5Rights Foundation observed in written evidence that the design strategies of online platforms “are based on the science of persuasive and behavioral design, and nudge users to prolong their engagement or harvest more of their data.

- Evidence demonstrates how some games, as well as social media platforms, use psychologically powerful design principles similar to those used in the gambling industry. Dr Mark Griffiths’s written evidence highlights how the structural characteristics of video games — the features that induce someone to start or keep playing — resemble those employed to keep people using gambling products, such as “high event frequencies, near misses, variable ratio reinforcement schedules, and use of light, colour, and sound effects.”230 Match-three puzzle games such as King’s Candy Crush Saga demonstrate reward mechanics in action: for example, the game rewards players with incentives, such as pop-up motivational slogans or free ‘spins’ that offer another random chance to win ‘boosters’ to enhance game-play, at random intervals.

- Similarly, design mechanics that encourage people to stay on, or return to, social media platforms include pop-up notifications delivered at random intervals; a lack of “stopping cues” to prevent people from reflecting on how long they have been using an application; and deliberately structuring menus or pages to nudge people into making choices that the platform favors.

- A slot machine handles addictive qualities by playing to a specific kind of pattern in a human mind. It offers a reward when a person pulls a lever. There is a delay, which is a variable — it might be quick or long. The reward might be big or small. It is the randomness that creates the addiction.

- Many researchers argue that digital technologies can expose children to bullying, contribute to obesity and eating disorders, trade off with sleep, encourage children to negatively compare themselves to others, and lead to depression, anxiety, and self-harm. Several studies have linked time spent on social media to mental health challenges such as anxiety and depression.

- Instagram has grown in popularity among young adults and adolescents and is currently the second-favorite social network in the world. Research on its relationship to mental well-being is still relatively small and has yielded contradictory results. This study explores the relationship between time spent on Instagram and depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and disordered eating attitudes in a nonclinical sample of female Instagram users aged 18–35 years. In addition, it explores the mediating role of social comparison. A total of 1172 subjects completed a one-time-only online survey. Three different mediation analyses were performed to test the hypotheses that social comparison on Instagram mediates the association time spent on Instagram with depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and disordered eating attitudes. All three models showed that the relationship between intensity of Instagram use and the respective mental health indicator is completely mediated by the tendency for social comparison on Instagram.

- Researchers inside Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, have been studying for years how its photo-sharing app affects millions of young users. Repeatedly, the company found that Instagram is harmful for a sizable percentage of them, most notably teenage girls, more so than other social-media platforms. In public, Facebook has consistently played down the app’s negative effects, including in comments to Congress, and hasn’t made its research public or available to academics or lawmakers who have asked for it. In response, Facebook says the negative effects aren’t widespread, that the mental-health research is valuable and that some of the harmful aspects aren’t easy to address.

- Body image is an issue for many young people, both male and female, but particularly females in their teens and early twenties. As many as nine in 10 teenage girls say they are unhappy with their body. There are 10 million new photographs uploaded to Facebook alone every hour, providing an almost endless potential for young women to be drawn into appearance-based comparisons whilst online. Studies have shown that when young girls and women in their teens and early twenties view Facebook for only a short period of time, body image concerns are higher compared to non-users. One study also demonstrated girls expressing a heightened desire to change their appearance such as face, hair and/or skin after spending time on Facebook. Others have suggested social media is behind a rise in younger generations opting to have cosmetic surgery to look better in photos, which has implications for physical health through unnecessary invasive surgery. Around 70% of 18–24 years olds would consider having a cosmetic surgical procedure.

- Many quantitative studies have supported the association between social media use and poorer mental health, with less known about adolescents’ perspectives on social media’s impact on their mental health and wellbeing. This narrative literature review aimed to explore their perspectives, focusing on adolescents aged between 13 and 17. It reviewed qualitative studies published between January 2014 and December 2020, retrieved from four databases: APA Psychinfo, Web of Science, PubMed and Google Scholar. The literature search obtained 24 research papers**. Five main themes were identified: 1) Self-expression and validation, 2) Appearance comparison and body ideals, 3) Pressure to stay connected, 4) Social engagement and peer support and 5) Exposure to bullying and harmful content. This review has highlighted how social media use can contribute to poor mental health — through validation-seeking practices, fear of judgement, body comparison, addiction and cyberbullying.** It also demonstrates social media’s positive impact on adolescent wellbeing — through connection, support and discussion forums for those with similar diagnoses. Future research should consider adolescent views on improvements to social media, studying younger participants, and the impact of COVID-19 on social media use and its associated mental health implications.

- The rise in popularity of instant messaging apps such as Snapchat and WhatsApp can also become a problem as they act as rapid vehicles for circulating bullying messages and spreading images.

- Cyberbullying can take many forms including the posting of negative comments on pictures and directed abuse via private messages. Almost all social networking sites have a clear anti-bullying stance. However, a national survey conducted by Bullying UK found that 91% of young people who reported cyber bullying said that no action was taken.

- Where teens and young adults are constantly contactable, and deal with online peer pressure.

Further Reading

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind — Yuval Noah Harari

- The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure — Jonathan Haidt & Greg Lukianoff

- Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions — Todd Rose

- Huberman Lab: Maximizing Productivity, Physical & Mental Health with Daily Tools — Apple Podcasts

- Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010 — Google Docs (research summary)

- Social Media and Mental Health — Google Docs (research summary)

- Status of Mind: Social Media and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing — Royal Society for Public Health

- Immersive and Addictive Technologies: Fifteenth Report of Session 2017–19 — UK Parliament Report

- Protecting Youth Mental Health — U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory, Vivek Murthy

- Teen Mental Health Is Plummeting, and Social Media Is a Major Contributing Cause — Jonathan Haidt, Testimony to U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee

- Beauty Filters Are Changing the Way Young Girls See Themselves — MIT Technology Review, Tanya Basu

- Research: How AR Filters Impact People’s Self-Image — Harvard Business Review, Javornik et al.

- Elon Musk’s Army of Inactive Followers Paints a Bleak Picture of X as a Whole — Mashable, Matt Binder

Leave a Reply